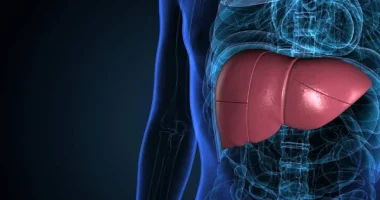

On Apr. 26, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) took a step toward formalizing the idea of adjusting gut-bacteria populations when it approved the first oral drug designed to treat the microbiome. Called SER-109, the pill is a cocktail of bacteria that can prevent recurring infections of C. difficile bacteria in people who have had previous episodes, and help them maintain healthy levels of gut bacteria. Keeping beneficial bacteria in proper balance could be an important way to keep disease-causing ones like C. difficile at bay.

The FDA based its decision on clinical trials that the drug’s maker, Seres Therapeutics, conducted in collaboration with Nestle Health Science in nearly 200 people who had had recurring C. diff infections. These infections spread easily in hospitals and are challenging to treat, since many of the bacteria are now resistant to antibiotics. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about one in six people who have had a C. difficile infection will have another one in two to eight weeks. About 156,000 infections occur in the U.S. each year, causing diarrhea, cramping, dehydration, and fever. Between 15,000 and 16,000 people die from C. diff annually.

In studies on which the approval was based, people took four capsules of SER-109 daily by mouth for three days to try to prevent recurrence of the infections. 88% of the participants did not have another infection eight weeks after a single course of treatment—the time period during which many infections come back—compared to 60% of those who received a placebo. Six months later, 79% of those who took SER-109 remained free of re-infections, while only 53% getting placebos did. The pills are given after patients finish a course of antibiotics to first kill as many of the C. diff bacteria as possible; the microbiotic therapy then helps to restore the beneficial bacteria.

“This could potentially transform how this disease is treated,” says Eric Shaff, president and CEO of Seres.

Until now, efforts to change the microbiome to address specific medical conditions have mostly involved fecal transplants. Studies have supported the idea that transplanting fecal matter from people with healthy gut bacteria can seed those good bacteria in the guts of people with less healthy makeups. But fecal transplants—which the FDA approved in late 2022 to treat C. diff—are tricky to develop and administer. Fecal matter is collected from healthy donors and treated in a series of purifying and sterilizing steps to ensure that only the desired populations of bacteria are transferred from one person to another, and it’s then given rectally. However, some recipients develop infections from insufficiently purified fecal matter, and questions about the balance of benefits and risks continue to plague the approach.

Seres’ product, which eliminates rectal administration, is also made from donated fecal material that is sterilized and processed—but in spore form to contain a combination of bacteria that only activate once they reach the gut. The recipe, which took the company nearly a decade to perfect, features bacteria from the Firmicute phylum, one of the dominant populations of human gut bacteria. Currently, the fecal material is collected from screened donors at a handful of Seres’ sites, and Shaff says it only takes a few dozen donors to supply what’s needed to potentially treat every U.S. case of C. diff.

Seres’ journey to approval wasn’t smooth. After positive early results in patients in 2016, the company’s second phase of testing, completed in 2021, was a disappointment, showing that most people did not benefit from getting the treatment. After adjusting the dose and the way that patients were tested for C. diff, the final phase of human testing produced more encouraging results. Those findings, which support the initial data from the early trial, were the basis for the FDA’s approval.

The approval opens the door to a new class of treatments for the microbiome that are easy to take and effective. Shaff says C. diff infections are only the start; the company is already testing another combination of bacteria, SER-155, that seems to prevent deadly infections in people who receive organ transplants. With the right combination of bacteria that can suppress populations of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, these patients could have a greater chance of battling infections and surviving their transplants. “If we see traction [with transplant patients], then we think there are opportunities in treating cirrhosis, cancer neutropenia, and other conditions where antimicrobial resistance is a problem,” says Shaff.

If the data on SER-109 and SER-155 continue to show benefit in adjusting the gut microbiome, then other infections might also join the list, such as urinary tract infections. “This approval is the tipping point for the field,” says Shaff. “We have the opportunity to treat patients with C. difficile infections, but that is by no means the end of the story.”