Deirdre McFarlane, intensive care matron

On 21 February, McFarlane, 57, was on her way back to Bangkok airport with her husband, Archie. The couple had been visiting their son, who works at an international school. “We felt apprehensive because the virus was starting to hit the news,” she recalls. She wore a mask at the airport and on the flight, though her husband refused. At Heathrow, nobody took their temperature or handed out hygiene leaflets, unlike in Bangkok. “You wouldn’t have known anything was wrong.”

They drove home to Westbrook, near Margate in Kent, where McFarlane works in the intensive care unit at the town’s Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother hospital (QEQM). On 25 February, she got up at 5.45am, and dressed in her work clothes. She remembers driving along the A28 to the hospital and thinking, “What am I coming back to?”

QEQM is a low-lying complex of buildings about a five-minute drive from Margate’s beaches. It serves a sprawling area that stretches from Dover on the south coast to Faversham in the north. Thanet has the highest number of people over 65 in Kent. Unemployment is higher than the national average.

QEQM has 400 beds, only nine of them in intensive care, where McFarlane has worked since 1998 – the last five years as matron. Normally in the intensive therapy unit (ITU) there are five or six patients; seven is really busy. They are attached to machines and tubes – intravenous drips, nasogastric tubes and catheters; there are echoing voices, bleeps and bright light. Mostly, though, for patients there is darkness. Being sedated helps them tolerate intubation – a tube in the throat that allows them to be put on a ventilator.

“We always talk to our patients, because we don’t know how much they can hear,” McFarlane says. “Besides, I like a good talk.” She is warm and friendly; slow to cry, quick to laugh.

Among the early patients to be admitted to QEQM with suspected Covid-19 was Archie, McFarlane’s 58-year-old husband, who works as a plastering contractor. Two days after returning from holiday, he developed a cough and his head pounded. On 1 March, she called NHS 111. “They said, ‘Stay at home, see how it goes.’ But overnight he became really unwell.” She looked at his feverish face and took him to A&E.

Deirdre and Archie were married in 1984, but have been a couple since they met at school, aged 15. Deirdre dealt with her worry by teasing him: “I told you you should have worn a mask on the plane!”

By then, only 36 cases of Covid-19 had been confirmed in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Archie was isolated on the respiratory ward; Deirdre had to self-isolate at home while they awaited the results. After five days, the test came back negative. But Archie had pneumonia and was in hospital for a total of 10 days. Deirdre was only allowed to talk to him on the phone.

On 6 March, she went back to work. Her diary started to fill with meetings on how to prepare for the virus. On 11 March, the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. “We thought, OK, so we need to isolate the patients and this is how we nurse them. And that’s OK, because we’ve got three side rooms.”

On 13 March the first patient with Covid-19 was admitted to the ITU: Ian Jameson, 51, director of a maintenance company and married with three children. He had type 2 diabetes but was otherwise in good health. He had come home from work two days earlier, feeling lousy; his throat hurt and he felt exhausted. He spent the next day in bed. Then the cough started. On the second day, he thought he’d cracked a rib because his chest hurt so much. His wife called NHS 111 and an ambulance took him to QEQM.

A chest X-ray revealed telltale “ground-glass opacities” in his lungs, fuzzy spots caused by fluid accumulating where his immune system was battling the virus. Doctors would later confirm that he had Covid-19 and double pneumonia. He was intubated, put on a ventilator and taken to intensive care.

Covid-19 challenged everything McFarlane knew about illness. “With flu or pneumonia, you see an improvement within a couple of days and this wasn’t happening. Covid patients deteriorated fast.”

Jameson was treated in a side room, away from the other patients. As the virus worked its way through his body, his organs started shutting down. He was put on kidney dialysis. He started to hallucinate, McFarlane recalls: at one point he thought he was the lower half of a Transformer, one of the Marvel superhero robot characters. “An element of delirium is normal in critical care,” she says. “But these patients are waking up to nurses who are gowned, masked and muffling through a visor.”

The next day (14 March), two more patients with suspected Covid-19 were admitted. A week later, there were 11 more cases in the unit. The next week, nine more. By the end of the first week of April, 51 Covid-positive patients were being treated in the hospital, including three more cases in the ITU. Planned operations had been cancelled. Families were no longer allowed to visit, with few exceptions.

McFarlane would toss and turn at night, her head spinning. She works day shifts, 7.30am to 5.30pm. Suddenly she wasn’t getting away until 9pm, and working six days a week; she also joined conference calls on her day off. Archie, who had by then recovered, took over the household chores, even cooking for the first time. She finished her day by sitting down to feasts: gammon, mashed potato, roast parsnips and corn.

There was a daily phone conference with senior leaders at 9.15am, to discuss bed space, PPE, staffing. Rules, procedures, policies changed almost daily. McFarlane converted five operating theatres and their recovery rooms into Covid-19 intensive care units, which required a lot more than simply moving beds and equipment. A “negative pressure” air system had to be installed, to allow air in but stop the virus escaping – and it all had to be done fast.

Even before the crisis, the ITU was short-staffed. As the pandemic hit, the hospital brought back critical care nurses who had retired, and redeployed nurses to the unit. Suddenly McFarlane had 99 extra staff who needed teaching. “We had one female shower, and that was a big problem because staff needed to shower and change their clothes before going home.” Nursing in full PPE – surgical gowns, gloves, masks, visors, theatre caps – would have been far easier if critical care had been contained in one ward. Instead it was spread across several areas and staff had to “don and doff” (a term that suddenly arrived in the hospital) their PPE before going into each area.

McFarlane says she never worried about catching the virus. “I was more concerned about keeping everyone else well and healthy.” The nurses got pressure sores from the masks, and not being able to take them off to have a quick drink brought its own complication: “There were a lot of urinary tract infections.”

On 2 April, Aimee O’Rourke, 39, a nurse at QEQM, died in the critical care unit – the second nurse in the UK to die from Covid-19. O’Rourke, who came to nursing late after having three daughters, had joined the acute medical unit at QEQM as a newly qualified nurse in 2017. She had been admitted to intensive care two weeks earlier. O’Rourke’s girls had been desperate to visit her, but by this time communication with families was via phone or iPad only. “Seeing your mum via an iPad,” McFarlane says. “I can’t begin to imagine how her daughters were feeling.”

McFarlane had worked in care homes and a hospice before becoming a critical nurse in 1998, and her concern for families is unmistakable. “When you’ve got experience with death, dying, you know what families need.” To see and touch and hold, she explains; to be there. “I had a woman recently whose mum was dying, not of Covid-19, and she said, ‘All I want to do is hold her. All I want to do is say goodbye. My heart is absolutely broken.’” McFarlane was able to nurse her dying mother at home, years earlier, and it hurt not to be able to comfort someone who couldn’t. Tears trickle down her cheeks. “I said, ‘If I could hug you I would. But I can’t.’”

When McFarlane got home at night, she would get in the hot tub. “I’d put the lights on and just chill. It was lovely. The stars and the birds, just beginning to quieten down. And obviously my husband would get in and we’d talk about the day. Not my actual day – just in general, like if the kids had phoned. I would never bring my work home.”

By mid-May there were only a handful of people with Covid-19 in critical care, and McFarlane had reconfigured the wards again: non-Covid patients in the converted theatres; Covid in the main ITU. A new critical care unit had been created, with 10 beds, ready for a second wave she still thinks will come.

“People are really fed up with social distancing, and it’s sad,” she says. She thought of how readily people once stood on their doorsteps to clap on a Thursday evening and how overwhelmed she was by that support. “But now I’m thinking, I don’t want that any more. I would rather they just stayed at home.”

Her mood by the end of May was “grumpy”. Crowds had gathered on Margate beach over the bank holiday weekend. “I wish I could bring them in here and tell them about the multi-organ failure, the pain, the invasive things we have to do to keep people alive. And how sometimes we can’t.”

By mid-June, the twice-weekly support group run by psychologists for staff to discuss their sadness and trauma had become a well-established part of the hospital routine. “It’s not counselling but it enables staff to reflect,” McFarlane says. “It’s not just the staff, it’s their children, too. They’re not sleeping, not eating.”

McFarlane had booked a trip back to Thailand for her 58th birthday, and a narrow boat for when the children came home over the summer. Both cancelled. “It doesn’t matter,” she says. “I live by a beautiful beach. I’d be happy to have a dip in the water.”

Last month, patients with Covid-19 were still being admitted – two into the ITU in the second week of June. To date, the hospital has treated 366 patients with confirmed Covid-19; of those, more than a third have died.

“It’s not over,” McFarlane says. The pandemic will leave many permanent scars, she adds. “Not being able to say goodbye in person is something relatives will have to deal with for the rest of their lives.” SW

Hatim Kapacee, primary school headteacher

‘Every day the government’s guidance was slightly different, and more confusing,’ says headteacher Hatim Kapacee. Photograph: Christopher Thomond/The Guardian

On the afternoon of 18 March, Kapacee, 54, could sense the tension in the playground of Heald Place primary school in Manchester. The anxiety of the teachers was mirrored by that of the parents at the school gates. The question they were all asking: why were schools still open? The UK death toll had exceeded 100 – a grim milestone – and headlines from the continent reported school closures in France and Spain.

Kapacee watched the pupils stream out, in their bright blue uniforms. People underestimate children, he thought; they were pretty good at taking even the strangest circumstances in their stride. “It was the adults who were afraid,” he says, “and I’m not discounting myself when I say that. But we didn’t sense any anxiety in the children.”

Parents and staff wanted reassurances Kapacee didn’t know how to give. “These were some of the hardest weeks,” he says. “I felt this immense pressure to do the right thing, but there seemed to be no definitive expertise to draw on. Every day the government’s guidance was slightly different, and more confusing.” He’s been a headteacher for more than 10 years, and knows that in a crisis his job is to rise above the anxieties of others and set an optimistic tone. “But I was scared, too.”

What the parents didn’t know was that he and his staff had been planning for closure since 11 March, when the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. Covid-19 was an agenda item in morning meetings, and staff began creating work packs for pupils, each containing half a term’s worth of exercises. “Though I suppose none of us really expected it to go on that long: who did?”

With the Whitworth Gallery and Manchester Royal Infirmary half a mile to the north, and the university’s Fallowfield campus a mile to the south, Heald Place is, in every sense, an inner city school. “We have 720 pupils, aged from three to 11,” Kapacee says. “So it was no mean feat preparing home learning materials for all of them.” Still, when school closures were finally announced on the evening of 18 March, he breathed a sigh of relief. The school would remain open for key workers; but this would be such a small number, he thought, that social distancing would be easy to enforce.

“But children naturally gravitate towards one another. On one of the first days after the closure, I came to greet a family. As we were chatting, I noticed the pupil was wandering behind the barrier we’d set up at reception. When I told her that she mustn’t, she said, ‘But I’m not dirty.’ It broke my heart. It drove home how hard it would be to make the children understand.”

On 19 March, the Department for Education announced a government voucher scheme for all pupils on free school meals. “I decided early on that we’d make weekly food parcels instead,” Kapacee says. “The closure process had started me thinking about our role in the community. I’ve always understood the importance of education in breaking the cycle of poverty.”

Kapacee’s own family had been expelled from Kenya in the 70s, and forced to find a new country as refugees. “We came to Manchester in 1975 with close to nothing; I’ll be for ever grateful for the opportunities a good education has afforded me. But I felt this time I needed to do something more.”

The country settled into lockdown, and Heald Place’s teachers began producing home learning resources. As the first collection day approached, the catering team set up socially distanced queueing systems and packed food parcels. And at 10am on 31 March, families started to arrive. “It was obvious that people were struggling, but I think that day everyone was putting on a brave face,” Kapacee recalls. The school implemented welfare calls, so each family had a weekly catchup with a member of the senior leadership team. “As April wore on, more and more worries surfaced: parents had lost jobs, incomes had ground to a halt.” By the end of the month, more than 200 families were accessing the food parcels. “We started to think about other things – personal care items, anything we could add to ease the pressure on household budgets.”

As Easter drew near, there were reports of a rise in domestic violence incidents. “That’s something we noticed, too,” Kapacee says. Many families in the school community live in extended groups, with in-laws, or two sets of families sharing one home. “These are pressure-cooker situations and it was heartbreaking to see the devastation. It’s not something I ever expected to deal with on this scale – even in families where you wouldn’t imagine violence to be an issue. I felt bewildered. Actions I might normally have taken weren’t available to me. And advice from higher up wasn’t forthcoming.”

The staff member responsible for child protection issues made socially distanced home visits. “In a domestic violence situation, even that weekly checkup can be a deterrent,” Kapacee explains. But far more useful, he thought, would be to get children into school, even for just one day a week. “We decided to switch to a rota system – different children on different days, so we could ensure distancing. We identified 90 vulnerable pupils and had about 70 accessing the in-school provision.”

But as soon as the partial reopening of English schools was raised in early May, “the whole situation seemed to crumble”. On 20 May, Kapacee received an open letter, from the National Education Union, Unite, Unison and GMB, pointing out that headteachers would be liable for any cases of Covid-19 in their school. “That kind of approach drove a wedge between me and my staff.”

For Kapacee, the government’s guidance amounted to: each headteacher will know what is best for their community.

“This is fine up to a point,” he says. But when he recalled his staff for a period of consultation ahead of the reopening, he found himself cast as the villain. “I felt very let down – by the unions and the government. People say headship can be a lonely position, but I’d never before appreciated what that meant. I did have to ask myself, ‘Why am I in this role?’” Each day briought up new worries. “My staff were caught in this crossfire between national guidance and the unions – trying to make sense of this new world and understand how it could work. As a leader, I felt almost out of control, and it was horrible.”

At night, he’d return home exhausted and emotionally drained; but by the end of the week he’d hammered out a system for getting reception classes and years one and six back into school. “This has been the biggest challenge of my career, but it’s only the beginning. We’ve had half a year of teaching taken out, and when all the children come back, we won’t just be focusing on academic standards – we’ll have to make sure their emotional and mental wellbeing is solid. That’ll take more than just drilling them with maths and literacy.”

In mid-June, Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford forced a government U-turn over free school meals during the summer holiday. It was a key victory, Kapace, says, though he’d made a holiday plan already: “We’d worked out a way to create mega food parcels that would last six weeks.”

The sleepless nights seemed to have paid off as he watched the first pupils make their way back into school on 15 June. Their excitement was obvious, and Kapacee was reminded again of how people underestimate children’s resilience. “Only 47 have been sent back in, a tiny proportion of pupils, so it’s hard to judge the full scale of the challenge in terms of their wellbeing and educational needs.” For now, he says, they will have to just “live” it. AJ

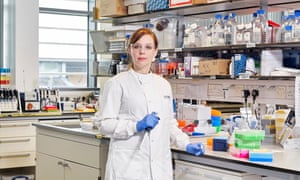

Christina Dold, vaccine scientist

‘It’s not a time to get your name on an academic paper. It’s a time to find a vaccine,’ says Christina Dold. Photograph: Suki Dhanda/The Guardian

When the Oxford team working on a Covid-19 vaccine first started holding weekly catchups in early February, Christina Dold, a 35-year-old senior postdoctoral researcher, jokingly referred to them as “Cobra” meetings. But it was in one of these early sessions that she found out how many volunteers they would be immunising daily, once the vaccine was ready to be tested. “I remember looking at a colleague. We were either going to cry or laugh, because the huge number of samples we’d have to process – potentially more than 100 a day – scared the living daylights out of us.”

There are about 250 people currently working on the trial – some from Oxford’s Jenner Institute, some from the Oxford Vaccine Group (OVG); Dold was pulled in because she runs an OVG containment facility. A vaccine trial involves taking blood samples from volunteers before and after immunisation; she is also working on a research project to understand why people’s bodies respond so differently to Covid-19. If a person involved in either the trial or the research tests positive, their samples are processed in her lab at Oxford’s Churchill hospital.

By mid-March, Dold’s work had settled into a rhythm. “When it came down to it, we realised this was something we had done a million times before. Not to toot our own horn, but we are pros at delivering clinical trials.” The OVG have conducted trials for vaccines against everything from malaria to prostate cancer to flu, and even a hypothetical, devastating “Disease X” humanity hasn’t yet seen.

As the human trials approached, the workload grew. Some colleagues were working from home and “Cobra” meetings became teleconferences, but Dold continued to go to the lab. She was starting before 8am, leaving after 10pm, then answering emails until midnight. Sleep deprivation was having odd effects. “You feel this tightness in the chest, think it’s Covid-19, then realise it’s just exhaustion.”

The mood at work was subdued. She was worried everyone working on the trial would get sick. “The day after we processed our first sample, one of my lab workers fell ill. Then another.” So far she has managed to dodge illness – no thanks, she says, to the official advice. “We had the BBC news on. Boris was telling us to wash our hands, and we were processing Covid-19 samples in protective gear and shouting at him. Then came the day a nurse messaged our WhatsApp group to say we had the morning off, because a participant in our research project – a patient at the John Radcliffe hospital – had died.” (No one involved in the vaccine trial has died.) “It really hit us. We cried. I phoned my parents and said, ‘I can’t do this.’”

On 22 April, the day before the first two people were due to receive the vaccine, adrenaline levels were high. Dold had at least solved her sleep-deprivation problem, through sheer exhaustion: “You know when you’re so tired you don’t even remember falling asleep?” Her boyfriend, Arran, was furloughed and baking a lot, and she felt guilty because her entire focus was on her team – plus she was working weekends. “It’s become acceptable to message colleagues then. There’s an unwritten rule that you don’t leave questions unanswered, because not giving information when it’s needed can create bottlenecks.”

The team was aware that more than 100 other vaccine trials were taking place in institutions around the world, but Dold says she wasn’t feeling under pressure. “Academia can be ruthless,” she adds. “Everyone wants to climb the ladder to be a principal investigator, but my boss Andy [Pollard, director of OVG] values people who get the job done, and we’ve taken on his attitude. It’s not a time to get your name on a paper – it’s a time to find a vaccine.”

By now, the team was working like “a well-oiled machine”. Something had to give, though, and that was clothes: “I’ve been wearing a tracksuit to work for the past six weeks. Not many people have followed suit, but then I’m not patient-facing.”

Towards the end of April, large numbers of people were due to receive the vaccine. Dold spoke to me from the storeroom where the protective equipment is kept, because she didn’t want to disturb a statistician working in their shared office. “On five days this week, large numbers of people will receive the vaccine,” she told me. “It’s happening right now beyond this door.”

The previous weekend, she had celebrated her 36th birthday. “Loads of people forgot, and fair enough, nobody knows what day of the week it is.” But Arran gave her flowers and baked a cheesecake.

Work continued to go smoothly. “At the last ‘Cobra’ meeting, you could feel the happiness and pride of the people from the manufacturing facility. They’ve worked so hard to produce enough vials of vaccine for the trial, and to do it on time.”

A high point was the bonding between the Jenner and OVG, two groups of people who shared a building but had previously kept a polite distance. No longer: “We’re in this big open-plan office,” Dold says. “You see people stand up like meerkats and call out to each other. Everyone’s found their equivalent on the other side and become friends.”

She was feeling the love from the wider world, too. One night in May she and a colleague delivered samples to the office of Sarah Gilbert – who is leading the trial – and noticed she had pinned up a dozen thank you cards she had received from the public. “We stood there reading them and were moved that people were aware of what we were doing. That they realised it wasn’t easy.”

By the middle of June, Dold was working harder than ever and the days were beginning to blur. The sense of urgency is ever present, though she won’t know whether their vaccine is effective until the trial is complete, many months in the future. “Our job can feel quite abstract. Before the pandemic, I was working on a plague vaccine and nobody thinks plague still exists. When all this ends, which is hopefully soon, we’ll go back to working on diseases that nobody thinks about.” LS

Yaseen Salah, homeless trainee blood technician

Yaseen Salah (not his real name) had been working in a restaurant and living in a hostel in Oxford: both had been forced to close because of lockdown. Salah says he was worried he’d end up sleeping on the streets. “I’ve slept rough before, and it’s not fun. It’s cold outside.”

Salah claims he avoided sleeping rough only when Oxford Mutual Aid (one of a number of self-organised groups set up to support people during the pandemic) found a stranger to put him up for a couple of nights.

South Oxfordshire district council eventually moved him to the Red Lion hotel in Henley, which was being used to provide accommodation for rough sleepers. “I was just glad to have four walls and a ceiling – it makes a big difference to have a room to myself,” he says.

Salah was born in Jerusalem, but grew up in Scotland and the home counties. He’s well-spoken, friendly and ambitious. The first time he left his family home to sleep on the streets, he was only 16. For the last three years, he has bounced around various hostels in Edinburgh, only returning home in December 2019 because he was concerned about the welfare of his younger siblings. But things soon broke down again.

Now, having spent nights on benches and in cramped hostel dorms, Salah was enjoying the “softest bed” he’d ever slept in, with the luxury of his own bathroom, an HD television, free evening meals and picturesque woods to wander around during his daily dose of allowed exercise.

The stability allowed him to start thinking about his future, and he applied to join the fire service. “I’m quite a physical person,” he says. “Working as a fireman would be a really positive change to my life.”

Salah recalls the hotel staff in their plastic gloves, looking worried, badgering people to follow the social distancing guidelines. Most of their new guests were behaving responsibly, but not all: “It’s the people who always have trouble. People well into their drugs, not looking after themselves,” Salah says. Three people were arrested after needles were found in their rooms. “They were stealing from other people’s rooms – they got taken away and didn’t come back.”

By mid-April, Salah had moved from the Red Lion to a Holiday Inn in Greenwich, London, and had been training to become a clinical support worker at the temporary Nightingale hospital at London’s ExCeL centre. At a session in the O2 arena, he learned “basic life-saving techniques” and how to use machines on the wards.

“This is the best, most stable environment I’ve been in for half a year now,” he says.

Salah has benefited from the government’s emergency “everyone in” directive, requiring councils in England and Wales to provide shelter for the homeless amid the pandemic. The government claims that councils have helped 90% of rough sleepers off the streets. Many are receiving three meals a day in hotels, and wraparound support to deal with mental health and dependency issues. But it has not been a complete success. In London, some authorities are reintroducing local connection rules, meaning rough sleepers who fled their home town for the capital are not getting help. The Guardian revealed in late April that around a quarter of the 200 or so homeless people put up in Manchester hotels for lockdown had left – some evicted, some by choice.

Two weeks later, Salah was told he wouldn’t get work in the Nightingale hospital as it had stopped admitting new patients. He applied for another position with the health service and began training to work in blood and transplant services, where Covid-19 treatment is being developed. As the plasma will be needed throughout the pandemic to help critically ill patients, Salah hopes he will have a steady job for a while. “I feel like I’m on the up,” he says in early May. “I’m looking forward to the next six months.”

In June the government announced that, as part of everyone in, a further £85m would be given to councils in England to help ensure homeless people did not have to return to the streets after hotels and B&Bs reopen in early July. Salah, though, has been hard to pin down. At one point he suggested over text to the Guardian that the transplant services job might be on hold. Then he stopped making contact altogether.

In July he suddenly got back in touch, and things were looking up: “After the Nightingale job fell through, I wasn’t allowed to stay at the hotel any more. I’ve moved back to my hometown, Didcot where I managed to rent a family’s converted garage at a bargain price. It’s my own place with plenty enough space. I’ve been paying for it through savings from my job at the hospital and furlough pay. I’m meant to be starting my plasma gig in a Stratford pop-up clinic in the next couple of weeks. I wouldn’t have got here if it wasn’t for the NHS.” DL and SH

The Guardian