Why does the Solomon Islands want a security pact? China announced Tuesday night that it had signed a security pact with the Solomon Islands. The agreement, Beijing says, is to promote peace and stability and runs “parallel and complimentary” to existing cooperation arrangements with the Solomons—an archipelagic country of almost 1,000 tropical islands and atolls, situated between Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea.

News of the pact came a day after the U.S. said it would send a delegation of senior officials to the South Pacific nation to convince it to scrap the deal. Led by assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs Daniel Kritenbrink, and the National Security Council’s (NSC) Indo-Pacific coordinator Kurt Campbell, the delegation had hoped to make the case that the U.S. could “deliver prosperity, security, and peace across the Pacific Islands and the Indo-Pacific.”

Concern is now mounting that the newly signed pact will give Beijing a foothold in the region. Last week, Australia’s Pacific minister, Zed Seselja, visited the Solomons and asked its leaders to “consider” not signing the agreement. He made the trip even though his government is preparing to fight a general election—by convention, a time when diplomatic outreach is suspended.

It’s rare that the South Pacific attracts such diplomatic courting. The U.S. closed its embassy in the Solomons capital Honiara 29 years ago, but in February this year pledged to reopen it. That same month, Antony Blinken became the first U.S. Secretary of State to visit Fiji in almost 40 years.

Behind the activity is the fear a new front has now been opened in the geopolitical rivalry between China and the West.

An unverified “draft” of China’s security agreement with the Solomons began circulating online late last month, causing a furore over its purported terms, which included the potential deployment of Chinese security forces to maintain “social order” in response to requests from the government of the Solomons.

Regardless of the document’s veracity, the response to it reflects deep-rooted concern over the future balance of power in the Pacific. As Dr Anna Powles, the New Zealand security academic who circulated the document, said on Twitter: “If it isn’t authentic, it still provides some interesting insights into how geopolitical dynamics are playing out.”

Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, an associate professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, tells TIME that “the manner and timing of the announcement” are significant. “Beijing unilaterally announced the signing just ahead of the U.S. delegation’s visit to Solomon Islands,” he tells TIME. “I think that is not a coincidence.”

Here’s what to know about the agreement.

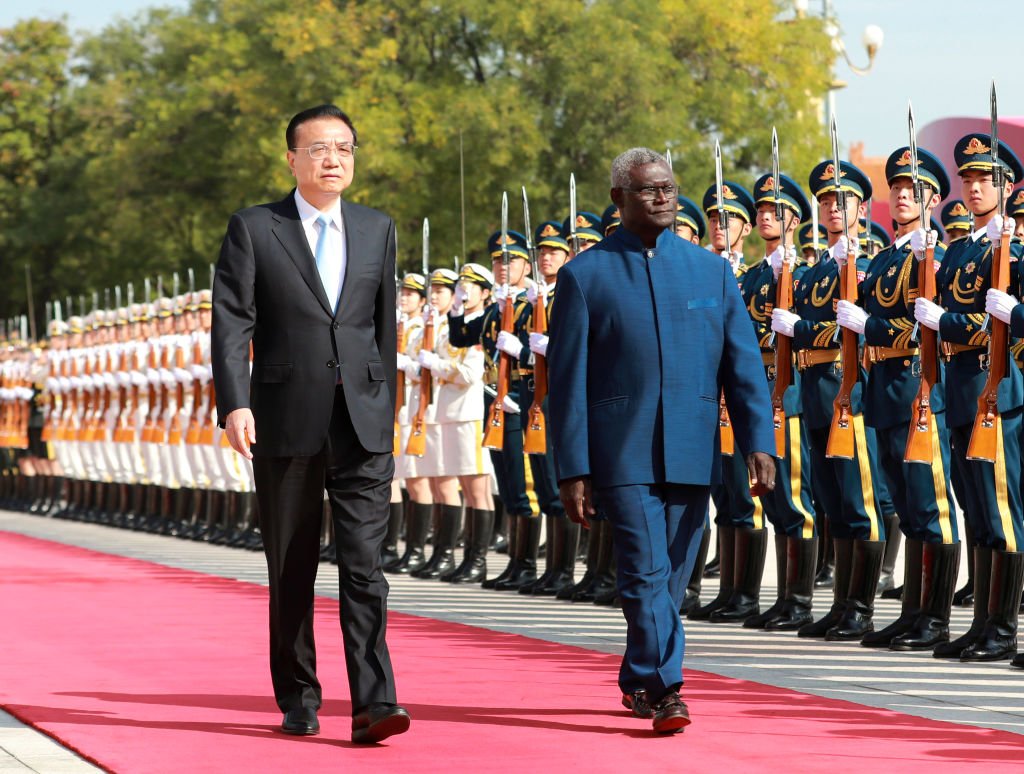

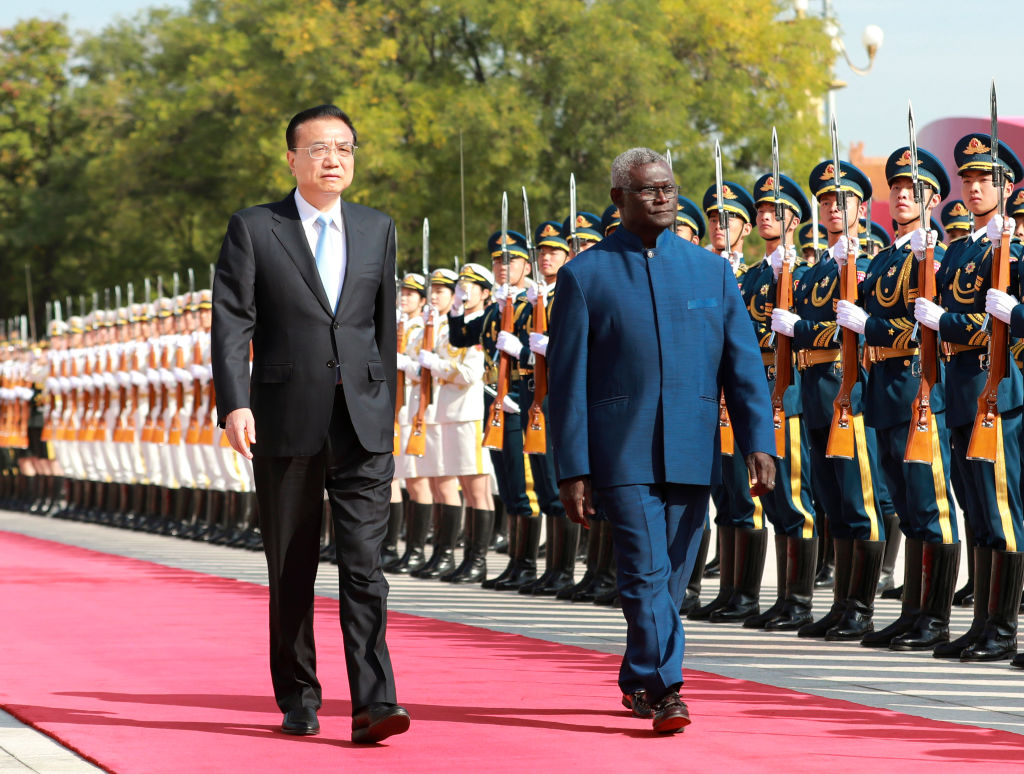

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang holds a welcoming ceremony for Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare ahead of their talks at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China, Oct. 9, 2019. Sogavare is paying an official visit to China. /Xinhua via Getty) (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei via Getty Images)

Why is there concern over the Solomon Islands pact with China?

State Department spokesperson Ned Price said on April 18 that the agreement left “open the door for the deployment of China’s military forces to the Solomon Islands” and “set a concerning precedent for the wider Pacific Island region.”

After the signing, an NSC spokesperson told Reuters the agreement “follows a pattern of China offering shadowy, vague deals with little regional consultation in fishing, resource management, development assistance and now security practices.”

Neither Price nor the NSC official cited the text of the agreement, which has not been made public.

New Zealand and Australia have also expressed concern over the partnership, because it might allow for a Chinese military presence in a region they have historically considered their sphere of influence.

Australia’s foreign affairs minister Marise Payne told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that there was “a lack of transparency in relation to this agreement.”

New Zealand’s leader Jacinda Ardern echoed the sentiment. “We see such acts as a potential militarization of the region and also see very little reason in terms of the Pacific security for such a need and such a presence,” she told Radio NZ.

But Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare of the Solomon Islands has criticized such responses. In an address to parliament on March 29, he said “We find it very insulting to be branded as unfit to manage our sovereign affairs, or [to] have other motives in pursuing our national interests.”

He added that the country would not allow China to build a military base, but at the same the Solomon Islands needed to “diversify” its relationships with “other partners.”

Canberra, which has a bilateral security agreement with the country, said earlier that it would continue to cooperate with the Solomon Islands, even if the pact with China was signed. But Prime Minister Scott Morrison faced criticism on Wednesday for not dispatching the more senior Payne to woo Honiara instead of Pacific minister Seselja. Penny Wong, the opposition party’s shadow minister for foreign affairs, told ABC News that it was the “worst Australian foreign policy blunder in the Pacific since the end of World War Two.”

Kabutaulaka says that the security agreement demonstrates that the balance of power in the region has been disrupted. “China is a power that is here to stay, at least in the foreseeable future, and has disrupted Western countries’ dominance of the region.”

Flames rise from buildings in Honiara’s Chinatown on November 26, 2021 as days of rioting have seen thousands ignore a government lockdown order, torching several buildings around the Chinatown district including commercial properties and a bank branch.

Why does the Solomon Islands want a security pact?

In 2019, the Solomon Islands switched diplomatic recognition to China from Taiwan, which China considers a breakaway province. Since then, China has been boosting economic ties, involving the Solomons in its signature Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, and promising to build a multi-million dollar stadium in the country ahead of the Pacific Games next year. Direct investment has also taken off.

“Chinese businesses dominate nearly every sector of Solomon Islands economy, from natural resource extraction to retail businesses and increasing assistance to the Solomon Islands government, although Australia is by far the largest donor,” says Kabutaulaka. “In order to understand China’s growing influence, one must understand the flows of Chinese capital.”

The response to China has been mixed in the Solomons. Last November, protesters demanded Sogavare step down for the 2019 decision to end ties with Taipei. The protests escalated, resulting in violence that saw several Chinese-owned businesses burned down.

The prime minister is sticking to his guns, however. Speaking on Wednesday, Sogavare said the agreement was necessary to cover “critical security gaps” and improve the ability of the authorities to deal with future instability. He added that the Solomon Islands entered the deal with “eyes wide open.”

Development plays a large part in the rapprochement between Beijing and Honiara. Tess Newton Cain, the Pacific Hub project leader at research center the Griffith Asia Institute, says that Sogavare believes Chinese infrastructure and investment are essential to the country’s economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“He’s very much made it clear that that’s what he sees as the economic path, or a significant part of the economic path, and there’s no question that China is very much the principal player in economic development of Solomon Islands,” she says.

Meg Keen, a professor at Australian National University (ANU), says that Pacific island countries see security and development issues as intertwined. “They want to see strong commitment from their development partners on the full range of security issues,” she tells TIME, “which include climate change, human security, resource security, as well as traditional security.”

Anti-government messages seen on a burnt-out building in Honiara, Solomon Islands, on Nov. 27, 2021, as a tense calm returned after days of intense rioting.

What are the implications of the pact?

While the pact undoubtedly gives Beijing greater presence in the Pacific, Keen points out “the signed agreement remains secret so the full implications are hard to judge.”

Newton Cain believes there maybe a domestic backlash. “The issue of lack of transparency is a concern in Solomon Islands as has been the case in relation to other decisions by the Sogavare government, including the ‘switch’ in 2019,” she tells TIME. Already, a senior opposition figure in the islands, legislator Peter Kenilorea Jr., is warning that the pact will “further inflame emotions and tensions.”

At the same time, the fact that the U.S.delegation to the Solomons is going ahead, Newton Cain says, is “a positive sign that Sogavare is maintaining communication and is available to hear from partners as to what their concerns are.”

Kabutaulaka says that the pact will spur greater Western engagement with Pacific Islands countries, already being seen in such initiatives as Washington’s Pacific Pledge, Australia’s Pacific Step-Up, New Zealand’s Pacific Reset, and the U.K.’s Pacific Uplift. The reopening of the U.S. embassy in Honiara is part of the same drive to counter Chinese influence.

“It is however unclear whether that will diminish China’s growing influence in the region,” says Kabutaulaka. “So far, it hasn’t.”